Subjective vs. Objective: Navigating the Transition with Universal Design for Learning

by Brian A. Dixon, Ph.D., Associate Professor of English, Goodwin University

The words that we use set a tone. Whether we’re having a friendly conversation or drafting a formal report, it’s important that the tone that we set is appropriate to the context. This is an important consideration in each of the English classes that I teach at Goodwin University, where students are engaged in the pursuit of clearly defined career goals. It’s certainly important in ENG 320 — Advanced Composition for Health Professionals, a course designed to prepare students for the kinds of writing that will be expected of them in a professional context. In addition to considering major themes in modern healthcare, the course’s writing assignments require students to think about the language that they use in their writing and the tone that they set with that language. One of the course’s primary learning outcomes is developing “the ability to write for an academic and professional audience, proving mastery of voice, diction, style, grammar, and mechanics.”

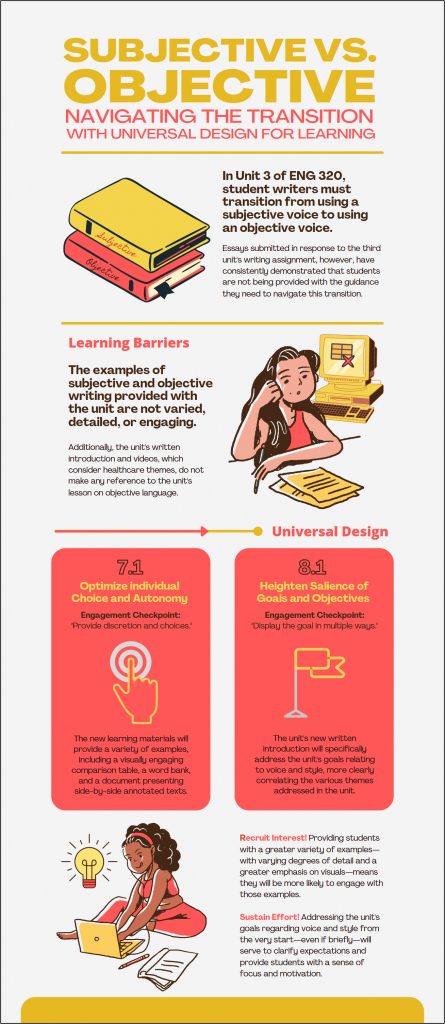

During the first two units of ENG 320, students are granted an opportunity to find their voice as writers in assignments that encourage a subjective approach: a self-reflective journal and a professional letter. These assignments often include personal narratives and passionate appeals. Unit 3 marks a point of transition, however. Beginning in the third week, attention shifts away from personal narratives and toward the semester’s final research paper, and the demands of the writing assignments shift accordingly. Specifically, the third unit’s assessment calls for student writers to transition from using a subjective voice to using a strictly objective voice.

As I sat down to grade the essays submitted during a recent online section of the course, I became aware of just how many students had not made this important transition. Many of these essays included language and perspectives that we would associate with a subjective viewpoint: “I think,” “I believe,” “I feel.” Even those essays that were predominantly objective in their approach sometimes used casual or informal language at odds with the tone expected in academic or professional writing: “What I mean is,” “To summarize what I am trying to get across…”

Student writers often employ such words and phrases reflexively, but they ultimately undermine an argument or analysis and the effect of including them is that the writing conveys mere opinions rather than critical observations and sound conclusions. This reflex can stem from their uncertainty as writers and critical thinkers or from a lack of previous experience with professional writing scenarios. Students are introduced to the distinction between the subjective and the objective in introductory English courses, such as ENG 101, but it was becoming clear that the learning materials included in my own course were not providing adequate support. With each new essay, I became more concerned that these students were not yet prepared for the greater challenges to come. In my search for solutions inspired by Universal Design for Learning (UDL), I have identified this as a critical event, a clear example of the kinds of learning barriers that could prevent our students from achieving their goals.

A close examination of the learning materials provided with Unit 3 considered in relation to the UDL Engagement principle serves to highlight several of these learning barriers. The unit includes a brief example of the differences between subjective and objective writing. The example takes the form of a comparison chart accompanied by sample sentences. The chart is limited and simplistic, however, and it has consistently proven ineffective at demonstrating the specific language that we associate with the two forms. Additionally, the unit’s written introduction and videos, which consider significant healthcare themes related to the body and identity, do not reference the lesson on objective language.

Two UDL Engagement checkpoints allow us to address these concerns, and considering them has led me to develop associated +1 UDL Engagement solutions for the course—small, manageable changes intended to eliminate learning barriers and positively impact students.

Checkpoint 7.1 establishes the need to optimize individual choice and autonomy, providing students with options and discretion. New learning materials developed for this unit must offer multiple means of engagement, providing a variety of different examples. These will include a more visually engaging comparison table, a word bank, and a document presenting side-by-side annotated texts. Students may choose to review any or all examples in preparing for the week’s assessment.

Checkpoint 8.1 suggests that we heighten the salience of goals and objectives, displaying specific learning objectives in multiple ways. A revised introduction for Unit 3 must address its goals relating to voice and style, demonstrating the connections between the unit’s various themes rather than simply assuming that students will be able to connect the dots.

It is clear that some students are not reviewing the examples currently available, and that the examples are not detailed enough to provide an effective model for those students who do review them. It’s important that the learning materials that accompany this unit recruit student interest. Providing students with a greater variety of examples will ensure that they are more likely to engage with those resources and, as a result, better understand their own use of written language. And while the instructions for the unit’s assignment stress the importance of developing an objective voice, the value of this goal is not emphasized or explored in other unit materials. As a result, the lessons may serve to divide or fracture a student’s attention rather than focusing it. The written introduction sets the tone for each unit in an online class, and it is key to sustaining student effort. Addressing the goals relating to voice and style from the very start, even briefly, will serve to clarify expectations, provide students with a sense of motivation, and improve focus.

As educators, it is vital that we reflect on our teaching practices and consider the ramifications of different modes of engagement. Evaluating the learning materials that accompany ENG 320’s pivotal third unit in association with Universal Design for Learning inspired more effective ways in which I might guide student writers in making the important transition from the subjective to the objective.

Click to learn more about Universal Design for Learning at Goodwin University.

Brian A. Dixon is an associate professor of English at Goodwin University and currently serves as Course Coordinator for Collegiate English. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Rhode Island, where he specialized in cultural studies in addition to serving as the assistant editor of ATQ: The American Transcendental Quarterly. His academic writings include studies concerning college writing centers, nineteenth-century American literature, detectives in film and fiction, ethnic humor in British sitcoms, the works of Ian Fleming, and the James Bond films.